A statistics course

committed to honest data analysis,

focused on mastery of best-practice models,

and obsessed with the dynamics of financial markets

Course Blog

Important: What Follows is the Course Blog for 2008!

This will tell you what happened last year in the course, but there is a new site for 2009.

Considering 434 for Fall 2009?

What you find below is the course blog for Fall 2008. If you are just now thinking about taking 434 next fall, you might want to jump down to a discription of the course prerequisites, etc. After that, you might look at some of the 2008 e-Handouts or read at random (from the bottom) in the blog. In the not-to-distant future, I will archive the 2008 blog, and start everything afresh for fall 2009. If for some weird reason you want to do so, you can even llook at the 2007 blog or 2006 blog. Things do change --- though never as fast as one expects (or hopes) they might.

Heads-up. The course is limited to 40 and that is the capacity of the room, so this course cannot accommodate auditors. Anyone attending the day one or day two lectures should be registered or on the waiting list.

Picking Up Your Final Projects?

The best time to pick up or discuss your final project is during my office hours, which for Spring 2009 are on Monday 3:00-5:00 and Wednesday 2:30-4:25.

It is a good idea to email me to make sure that I know when you are coming.

Surely, I will be in the JMHH 400 suit but I could be in the conference room or in a colleague's office.

Grading Epiphanies ...

I am working through your papers, and learning some new facts --- or potential facts. Here are some to consider:

- If you consider returns on spreads, like the return from being long XLF and short SPY, then in "low volatility times" you have decent trend following but in"high volatility times" you have much less trend following --- and by randomness, even some mean reversion.

- Our favorite Garch(1,1) in noise AR(1) in mean model looks like it can be beaten at least some of the time by using EGarch+AR(p) for p=2 or p=3. In particular, this seems to be with winner with energy service MLPs, but it also stood up well in other situations.

- I have seen a number of papers that did a lot of work to incorporate transaction costs into their analysis. This is a noble thing to do, but one really can get to the essence of the issue with some pretty simple rules of thumb. I have written a page on this for the benefit of future students. Take a look and see if it is consistent with your experience.

- Forget the means? Some papers found promise in strategies that used portfolios that were driven just by the conditional variance, letting go of the means entirely. This is a nice spin on ordered univariate strategies that traditionally use Sharpe ratios, Kelly fractions, or means corrected by volatility drag

- Some papers combined the ideas of Kelly betting and Ordered Univariate Strategies. As a generic version of this idea, consider the eight sector SPDR, model them individually, then rolling forward, get conditional forecasts of next period mu and sigma. Look at the Kelly fractions, but don't bet on all of the series in a Kelly way. Instead, just look at the"best half" of your potential bets, and then use the Kelly fractions in some way to be on just the "good half". This seems to be a promising general approach.

- Das and Sun tried a nutty idea that seems to have worked. In a Markowitz context where one uses the "stable correlation and less stable standard deviations trick" --- they replaced the correlation with Kendall's tau. This weird idea would never have occurred to me since Kendall's tau does not have the same probabilistic interpretation as correlation ---- it's just a similarly scaled measure of association. Doggone it, if the tau based methods didn't out-perform the "natural" methods. There is definitely a mystery here.

- I'll add more as I keep working through the stack. I hope to post the grades before the 25th.

Repeat --- Project Due Date: Noon Wednesday Dec. 17

- My mail box in Suite 400 JMHH or under my door in Room 447.

- ALSO a copy by email --- the copy should be marked "OK to Web Post" or "Not OK to Web Post". Please put this information on the first page of the PDF. Incidentally, I prefer PDFs to Word or other document types.

- You must provide both a hard copy and an electronic copy.

- Please name the PDF of your electronic copy BY YOUR NAMES.

- Not something like Stat434 Final! --- for obvious reasons.

- Late projects are penalized at one letter grade per day. This is a huge penalty. Don't consider it for a moment.

Project Advice --- the End Game

Anyone who works on any project will face questions that were not faced before the serious work on the project began. This is natural and good.

Unfortunately, at this stage of the game, I am hesitant to provide tons more coaching. Naturally, if you are really stuck, I am happy to help, but if you are just facing some of the blizzard of alternatives that any analyst faces once the work has begun --- well, in that case, it really is most appropriate that you to make your best choice and use your report to explain why you decided what you did.

After all, you are a reasonable person. Why should your decision not be something upon which real people would wager real money? In fact, arguing for your ad hoc decisions a way to win "points" on your project.

Wise decisions are --- after all --- the real force behind what one gets paid!

"Stunning Fraud of Epic Proportions" (12/11/08)

Bernard L. Madoff, septuagenarian Wall Street asset manager, gave it all up at the office today by allegedly telling employees that it was all a "giant Ponzi scheme."

It is murky now, but there is talk of as much as $50B missing from clients' accounts. I can't see how auditors could fail to see even a few million missing from client accounts, so it may well be that Mr. Madoff just went off his meds for a couple of days and things are mostly OK.

Let's call that the PollyAnna Point of View. What else can I cling to?

If the $50B number holds up, it will be a world record. Robert Vesco netted less than $200M and he came close to toppling at least a couple of governments.

Over the next few days there will be some strange distortions due to asset freezes, etc. There will also be some very sad statements from famous NYC charities that were high on the sucker list.

Got a Bucket?

Contango Profits are the highest in a decade. Buy oil at spot, sell the March futures and deliver the oil to satisfy the contract. You'll make an annualized 38%. This is a form of madness. The bottom line is that the spot price of oil is at least a little bit goofy. (12/7/2008).

Great Graphic --- 2008 is Different

Greg Mankiw's Blog is almost always interesting, but on 12/7/2008 he has a stunning "augmented histogram" that shows just how remarkable asset returns in 2008 have been. Do take a look. In addition to the story the graph tells about this specific data, it illustrates a very powerful principle --- even the most humble graphic can be improved. It certainly is a delight to see the (usually horrible) histogram get this nice make-over. [Thanks are due to Blake McShane for passing along this great link.]

Presentations All Done!

This was a very well prepared sequence of presentations that showed knowledge, hard work, and honest thoughtfulness. I was impressed!

Moreover, I am sure that the final projects will live up to the high expectations that the presentations have created, so I will have lots of work (but lots of fun) reading your final reports.

Lost and Found:

One very nice tea thermos was left in class on Wednesday. It can be picked up from the Statistics Department information desk during business hours anytime for the next few days. After that, it will be sent to Wharton Lost and Found.

Not Entirely Redundant --- EDA & a Gallup Poll

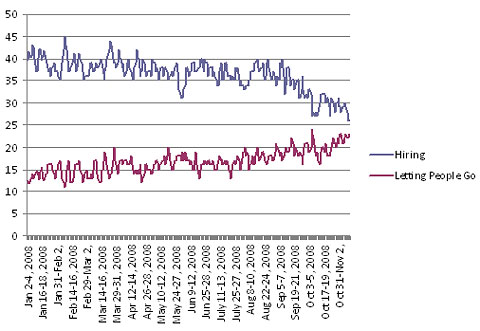

The punch line here the question: "Based on what you know or have seen, would you say that, in general, your company or employer is — 1) hiring new people and expanding the size of its workforce, 2) not changing the size of its work force, or 3) letting people go and reducing the size of its work force?” (source NYTs, 11/29/08)

This question is asked in repeated polls of a sliding panel --- an intelligent design. The Blue and the Purple lines taken together are perhaps a little redundant, but they are not entirely redundant. The residual sum gives the "not changing" value, and this is useful information.

Can you think of a better plot? Is it curious that the "not-changing" value is nearly constant? I'd have guessed that it would be as volatile as any other piece of the picture.

Sidebar: Promised Link on "Zero Cost" Portfolios

Naturally, they are not zero cost, or why would we hold anything else, since some of these do indeed have positive expected returns. The arithmetic of returns is a little tricky here. I've made one pass, perhaps you can do better. At least this puts some issues on the table.

Sidebar: 130/30 Strategies

It's been kicking around for ages that one might do better to be 30% short and 130% long. You can find a lot about this idea on the web. JAI has a useful empirical piece that is easily accessible.

Day 24: Project Proposals --- First Day of Presentations

For 26th November 2008

The presentations today were all excellent. They showed thoughtful preparation, energy, and originality. They set a high bar for day two and three!

The scheduling also went without a hitch, and we had a good crowd for the Wednesday afternoon before Thanksgiving. Wharton staff left at 2pm, but we kept plugging to 3pm and beyond.

"Will We See a January Effect This Year?"

Mark Hubert has a nice piece on this. His bottom line is that the January Effect (i.e. bigger small cap returns than big cap returns from 12/15 to 1/15) is more pronounce in years where the market has been strong going into December.

That is decidedly not this case this year, so you might expect to have a small or non-existent January Effect. Humbert's analysis is based on "correlations that would convince even skeptical statisticians." Humbert's suggestion would make for a good EDA project, but unfortunately it does not fit well with our time series mandate.

Strange Yield Curve (11/28/08)

The 5, 7, 10, and 20 year treasuries are now 4.17% 3.78% 2.60% and 2.98%. This means that if you buy the 10 year, and the yields don't change, you will ride "down" the yield curve to a bond that yields 128 bp more. This is very bad news. Approximating the duration to be 5, your bond price goes down 6.4%, thus eating up your entire three years' of "coupons." The ten year US Treasury has never looked so bad. The only scenario that makes this make sense is ... well, deflation may do it, but that's pretty hard to believe.

AbnormalReturns --- A Fine Meta Site

The Abnormal Returns Blog does an excellent job linking to insightful articles on the web. It is almost always worth a daily look --- or at least a weekend review.

Factoid on Mean Reversion in the Long Run

If you are searching for some reason why we might get back some of the money that we have lost this year, it is worth noting that the "twenty year variance is just 45% of what it would have been if annual returns were uncorrelated" (cited by Delong, page 7 footnote.) Unfortunately, this also means that the twenty year standard deviation is just 67% of what it would have been. This sounds like less of a bargain. Still, we do have a little mean reversion baked into the cake. It's also worth noting that DeLong is writing about real returns.

Will Quants Beat Non-Quants in 2009-2010?

There is a piece from Washington Asset Advisors that argues in favor of the technical vs fundamental view. Who knows if it is right? My own confirmation biases push me in the direction of agreement. After all, it's what I want to hear.

Pedro Aspe

I could constantly plug Knowledge@Wharton, but you know I don't. Still it has some great coverage of a recent presentations by Pedro Aspe. This article is worth a quick read, even as the time shortens for your proposals and projects!

Citi Saved --- At Least For a While.

As you ponder your papers, it is perhaps nice to note that the $300B agreement between the US Government and Citigroup was done in four pages. I made a good trade here, but I admit that I was gambling.

Quality Computational EDA : BooksThatMakeYouDumb

If you have good computational chops, you may look at the design pioneered at BooksThatMakeYouDumb. I think it is an interesting social search model that tells us something about the world. You may be able to do the EDA better. It would certainly be interesting to replicate in other languages/educational systems --- e.g. France. Naturally, you have to think harder than this author did about the nature of the sampling bias. For example, large state schools will tend to have (1) lower SAT scores and (2) a more diverse collection of mentioned books. Also, it goes without saying that the inference in the title "BooksThatMakeYouDumb" surely has the inference reversed, if indeed there is any inference to be made at all.

Day 23: Putting the Pieces Together

For 24th November 2008

Today we will have completed just under two dozen lectures, and this is a very modest number given our goal of dealing honestly with one of the central factors of economic life --- the returns on financial assets.

Our plan for the day is to (1) review the stylized facts that we have verified from our own analyses --- and add a few new twists (2) review our models with a focus on where they add insight and value, and finally (3) look at a few ways these can inform the design of interesting projects. In particular, we'll look at the interesting distinction between univariate, multivariate, and ordered univariate strategies. Variations on these methods can be applied to almost any basic project idea.

I'll also add a word or two about the use of confidence intervals and suggest a new technique --- bootstrapping ---which you can use to get confidence intervals (of a sort) for the return on a trading strategy. The method is not perfect, but it definitely has its charms.

I'll also ring the bell again about the importance of data cleaning, EDA, and presentation with thoughtful tables and graphs.

Generic Advice about Project Design (and Process Comments)

Certainly read the Final Project Spec Sheet. I'll review some of the main points in class. The one I would underscore here is that clear thinking is a key to having an excellent report. You want to make clear assertions and you want to make sure that what you assert is backed up by clear, thoughtful, and thorough research. Even a "simple" theme can lead to a very rich report if it is engaged carefully and completely.

Pre-proposal Two Pager --- Due Monday 11/24

Everyone should hand in their two-page pre-proposal sketch on Monday November 24. This will not be "graded" directly but it will help me be up-to-speed when Proposal Presentations begin on Wednesday.

I may not have made this timing perfectly clear, so if you really can't give me anything on Monday then please email me your two pager on Tuesday.

Sidebar: "It's Morning in America"

About 25 years ago, Ronald Reagan was running for his second term, and his campaign produced an ad that has become a classic. UTube makes this classic (and many other moments of teary nostalgia) just a click away.

It is soapy, and nationalistic, but it is also brilliant writing that evokes emotion and gets votes. I am sure that one day again there will be an incumbent president who can again run on a record of achievement and integrity. I just hope it doesn't take a quarter of a century.

Sidebar: Was Marx Right? (Posted 11/20/08)

No, I don't believe for a moment that democratic capitalism is busted, but after losing 13% in two days, I did think I might be cheered by listening to a few rounds of the International. I warmly recommend its definitive MP3 site. The International is there in all languages, but I prefer the Russian or the French just for historical reasons.

The best anti-Marxist argument I can think of right now is that people must trust our government a lot if they are willing to buy the 1 year note with less than a one percent yield.

Sidebar: Dollar Weakness and Stock Market Returns?

A while back there was an instructive piece in Business Week on the relationship of the strength (or weakness) of the dollar to the returns on US equities. The article looks at changes (or returns), not levels, so it avoids a the classic spurious regression slip. The use of monthly data and the shortness of the series make it hard to put the article's inferences into the domain of stylized facts, but I would expect that there are observations here that will stand the tests of time

Sidebar: Wikipedia on the VIX

The Wiki piece on the VIX is pretty good, maybe even very good. You might test how often the VIX really does correctly forecast the next month absolute change.You could think about this in concert with the little volatility paper by Goldstein and Taleb a look at their paper. Yahoo!, may the name usually be cursed, does offer nice VIX graphics. Still, what is the logic of the log scale here?

Sidebar: Bear Stearns Preferred

The common stock of Bear Stearns was virtually wiped out in the sale to JPM, but the preferred shareholder got a notably sweet deal. Their shares were converted to JPM Chase preferred shares with essentially the same terms as the original Bear Stearns shares. That was one hell of a fine boost to the credit quality.

Now (11/22/08) if CitiGroup is forced into some combination, it is a natural bet that the preferred shares may escape unscathed --- or even enhanced. Given that they now trade to yield 20% or more, they look sweet --- conditioned on getting paid either by CitiGroup or by some surviving entity.

The fear of course is that that preferred shares can be clobbered; most FNM par 25 preferred now trade about between one and two bucks. Even that is a mystery since the coupon payments have been omitted.

Note: The cash injection and asset back up today (11/24) may make this speculation mute, but the general principle is still worth keeping in mind.

Sidebar: No Juggling This Year?

Traditionally I have used the day before Thanksgiving as a day to do some "odd" things. One topic has been to see how good you would have to be to justify playing in the World Series of Poker. The bottom line is that after accounting for the decreasing utility of long-tail returns, you'd have to be better than probably anybody has ever been. If you include the asymmetric tax treatment for non-professionals, it is certainly a bad deal --- unless you get $10K of fun losing (which I hope you don't).

The other topic that has served us well on the day before Thanksgiving is to show how learning to juggle with three balls can be a useful metaphor for learning any complex task.

Also, three ball juggling can be very beautiful --- and magically complex. We won't "cover" it in class, but there is no better way to have four minutes of fun than by watching the Fugly Beatles set.

Finally, there is our traditional strutting turkey ---- Oh, what he does not know? Sort of reminds me of Bear Stearns's James Cayne going off to his famous bridge tournament.

Day 22: Comparing Asset Returns in the Context of Risk

For 19th November 2008

The plan for today is to look at the notion of risk adjusted returns from soup to nuts. This is a very interesting topic in financial time series, and it has been developed far less systematically than one might have guessed. We'll consider all of the conventional measures, and add a few variations of our own. We'll also look at what one might learn about risks by consideration of post-mortem analyses of crises and crashes.

Sidebar: TradeSports Closes Its Doors

TradeSports.com was an extremely successful futures market for political and sports events. Since the contracts were on binary outcomes, the futures prices had an immediate interpretation as market estimates of probabilities. These futures markets were much loved and much followed, but the ludicrously named Port Security Bill made transactions with TradeSports so cumbersome that they have decided to shut down their business and refund all money in the client accounts. This is a sad day for libertarian investors who are willing to place a bet on their view of the likelihood of a political event.

Note: We will (probably?) continue to have the Iowa Election Markets, but these were always very thinly traded compared to TradeSports.

Note: InTrade (the non-US parent) of TradeSports seems still to be open, so this is an on-going story.

Sidebar: The Risks of Being in Charge of Risk Models

Things do have a way of periodically blowing up, and now banks have found the natural goat -- the guy in charge of the VaR models. (see story). Reminds me of some advice I once gave a class of Wharton undergrads...

Sidebar: Volatility? What Volatility Are You Talking About?

When I saw the title of the paper " We Don’t Quite Know What We Are Talking About When We Talk About Volatility" by Daniel G. Goldstein and Nassim Taleb, I was quite excited.

At last, I thought, someone is making the point in print that I have made repeatedly in class. Namely, each time we say "volatility" we point to some parameter in some model, but the model and the parameter can differ from utterance to utterance. This is silly of us, but we all do it.

Goldstein and Taleb get a whiff of this, but not the full scent by any means. Still, you should take a look at their paper. It is a quick read.

Sidebar: PDP a Momentum ETF

PDP is a PowerShare ETF launched in March 2007. The prospectus is one that would make Jessie James uneasy. Unfortunately this asset has not been around long enough to be amenable to much analysis, but the underlying theory of the asset is interesting. It is a momentum story based on a proprietary momentum index --- which would all seem insane --- except that the proprietary index is published independently of PowerShares. Still, the index provider does not seem hesitant to be a promoter of the ETF. Net-net, this does not look like a healthy development.

Sidebar: Nice EDA --- Two Regions Each with Ten Sectors

If you take the 10 sectors of the SP500 and the 10 sectors of the MSCM EAFE you get 10 pairs of numbers, one for each sector. You can then plot these pairs in two dimensions and then ponder the meaning of the 45 degree line. Lo and Behold! It tells you in which of the two regions the given sector is now doing best.

This gives a very interesting snapshot of current market "stages." Note: Points that are near the line are doing about as well in each region, so not much "weight" should be placed on these points. Still, each one of these points deserves a story.

Note: The graph below is for November 2007. Oh, how sweet those returns look to us today! They are almost all positive for Pete's Sakes.

I would love to see the dynamic analog of this graph, even for just one sector. The graph I have in mind would plot (x_t, y_t) where, for example x_t is the period t return on the EAFE energy sector and y_t is the period t return on the US energy sector. We could look at 3 month trailing returns and plot a point for each week. It could be a very informative picture.

Sidebar: Stupid Forbes Article

There is a Forbes article exactly on today's topic, and it illustrates just how shallow magazine articles can be. Here we can see the shallowness so easily, the article can cause us no harm. What scares me is not this article, but all the ones that I read where I think that I have learned something new.

Sidebar: Yet Another Black Rock Insane Bandit Fund

The Black Rock Fund Equity Dividend Fund (class A) MDDVX , has a front end charge of 5.25% and a turnover ratio of 2%. If you like this asset, just check the SEC filling, get the holdings, and voi-la 98% replication. This is a dominated asset with 750M under management. They should be ashamed of themselves. Oh, by the way, they have 100bp expense ratio, and --- a Morningstar rating of 4 stars --- which pretty well tells you how worthless Morningstar ratings can be.

What a bizarre situation! Well, small turn over may be virtue in some people's view, but why should anyone pay and annual 100bp for the experience?

Sidebar: Michael Lewis on "The End of Wall Street"

Michael Lewis is famous for his book Liar's Poker which chronicled the goings on at Salomon Brothers during the "Wall Street excesses of the 80's" which were actually pretty tame by contemporary standards.

His current piece is provides a compelling view of the sub-prime development and how if you had a brain and intellectual integrity you could have been on the right side of the trade of the century.

It is one of the most riveting pieces of financial journalism that I have read in years.

Sidebar: RiskMetrics on Volatility

The November 2008 research letter from RiskMetrics is worth a look. It's naive in many ways, but it does start some interesting conversations.

Day 21: Cointegration and Statistical Arbitrage

For 17th November 2008

Final Project --- The Full Details

The project specification has evolved over more than five years of experience, so it is hard to imagine the there is any ambiguity that remains to be squeezed out. Still, I do want to go over it to make sure that everyone knows exactly what is expected --- especially at the level of academic integrity.

Do not forget that your final report is due at NOON on December 17. You must deliver a hard copy to my mailbox in JMHH Suite 400 and you must send an electronic copy to my email. Both forms of submission are required. Late reports are penalized at one letter grade per day. This is a huge penalty. Don't even think about it.

You should note on the hard copy and the electronic copy if you are willing to have your report posted on the web for the possible guidance of future 434 students. Without your authorization, your report will not be posted, even if it is the perfect model for a 434 final project report.

***Schedule for the Project Proposal Presentations***

Main Business --- Cointegration and its Application

The plan is to develop the theory of co-integrated series and the application of cointegration to statistical arbitrage. There are many of variations on this theme, but we will be particularly attentive to pairs trading. This class of strategies has bought more than one nice house in Connecticut, but its popularity has repeatedly waxed and waned.

The Puzzle that Started Cointegration --- Spurious Regression

We'll begin with one of my favorite simulations. Simulate two independent random walks, store the values in vectors x and y, regress y on x, and WHAM --- you find a highly significant alpha and beta almost every time. Since we know that x can not tell us anything useful about y, we know we have a spurious regression.

Next, we'll look at the way out of the trap --- testing that the residuals are an I(0) process. If the residuals are an I(0) process we are safe (or at least in no more danger than usual). If the residuals fail to be an I(0) process, then we almost certainly have a garbage regression. It is amazing how often you will see people perform such regressions, not knowing that they have fallen into a well known trap.

We'll look at some resources that add further intuition to this process, including the famous "Drunk and Her Dog" story.

Finally we'll look at some ideas from statistical arbitrage including the idea of a synthetic index and methods of pairs trading. I've started a resource page on pairs trading and I will add to it over time.

Sidebar: News Impact in the Classical Sense (Kobe, Katrina, and Crisis)

How much does news move the markets? This is the question that is addressed by what are called event studies, and there is a nice summary of some of these in a popular article by Robert Shiller, who is well-known for his book Irrational Exuberance.

Oddly, the Kobe scenario was one of "bad news travels slowly." The day one reactions were minor, but after ten days the Nikkei 225 had fallen by more than 8%.

One of Shiller's theses is that market impacts are sometimes the result of news cascades; that is, a drumbeat of follow-up news stories can have more financial impact than the initiating event. Since Katrina was post the publication of Schiller's essay, you might see if Katrina fits into his mold. This won't really make a whole project for the final, but it would be a nice investigation to share with the class.

This theory of news cascade also seems relevant to the financial crisis of 2008. Lehman hits the tank, AIG gets massive, bail out, GM hangs by a thread, etc. etc. It's hard for the market to rally if the world keeps presenting a cascade of bad event that are all related and all on a glide path that takes many months to run.

Sidebar: China Share Classes

There is a brief article on Red Cat Journal that discusses the various classes of Chinese equity shares. We may discuss these as part of our conversation on "how to frame your final project." There is also a follow-up piece at Red Cat that opens a conversation about the eventual convertibility of the share classes. (My thanks to "Phoebe" Fei Gao for these links.)

Sidebar: KMP vs KMR

Kinder Morgan is the largest pipeline management organization in the US. Investors can participate in Kinder Morgan either as limited partners in the MLP with symbol KMP or through another vehicle which is a kind of management company that trades under the symbol KMR.

There is a comment at Morningstar that argues that these assets should trade in "lock step." To me it seems interesting to look at the time series properties of the spread on these two assets. You'll want to think about what is really going on with the two, and you will need to keep in mind that it is particularly awkward to short KMR, i.e. it may be practically impossible. Still, if you get amused by MLPs this is where the fight begins.

Sidebar: Details on a Blackrock Bandit Fund

People who have been ripped off are understandably thin skinned, so if you have an uncle who has been conned by some retail Merrill Lynch account representative into buying Black Rock Equity Index Fund CIEBX --- or something similar --- you have to be gentle as you coach your uncle out of the jam.

Now would be a good time; the capital gains are not likely to so large that taxes will be a worry.

The objective of the CIEBX fund is "to match the performance of S&P 500 index" and--- provided that they mean the total return of the index holdings rather than just the index price return --- this is a noble goal. Unfortunately, they have a" deferred' front end load of 4.50%, a 0.75% 12b fee and 1.17% expense ratio.

In a world where you now pray for a 4% real return, buying this fund throws away about half of the real return you hope to learn. Buying it is just like giving away half of your future real earnings --- or half of your initial investment.

Buy 100K of this fund, and asymptotically you are guaranteed to get a negligible fraction of what you would get with an investment in an honest SP500 Index Fund such as Fidelity Spartan or Vanguard Admiral. This isn't fancy theory; it's arithmetic. Saving your Uncle from this mistake for just 100K will over time save enough to pay for someone's full Wharton education.

Why Do They Do This? It's NUTS!

What I don't understand about Merrill Lynch and Blackrock is why they don't care more about the reputation risk that this kind of larceny at the retail level creates even at the wholesale level. It is transparent that the CIEBX fund is a crass rip-off. Other products are harder to analyze, but, if they are willing to rip you off when you can check exactly how much you have been scammed, then you have expect that they are REALLY ripping you off with their more obscure products.

Do People Learn? Evidently Not

" In 2002, Merrill paid $100 million in fines after regulators found analysts at the firm had recommended stocks they knew to be no good. "(ref)

Still, in every township throughout the land, one can find the friendly well-meaning ML rep, often clueless to his complicity, plugging products that under every possible future scenario will leave his clients with less money than they could have had if they had taken the time to read the prospectus and compare the ML products with the corresponding products from Fidelity or Vanguard.

Sidebar: Details on TIPS

There is a piece from GE Asset Advisors that provides a good tutorial on TIPS. It covers the mechanics and discusses both the strategic and tactical uses of TIPS. In a world where there is the possibility of deflation as in 2009Q1, there are some interesting twists on TIPS. Incidentally, they are a favored asset of David Swensen.

Sidebar: The Once Noble CREF is No Longer a Hero

Funds like Black Rock Equity Index Fund CIEBX are rapacious in their greed and exploitation of the credulous, but I am almost as irked by CREF.

In the early days, CREF was a genuine leader in providing investment value. Accordingly, they won a place close to the heart of academia. Sadly, in the last ten years, CREF has exploited that trust, and it now charges fees that are indefensible.

The CREF Equity Index Fund expense ratio is 0.50%, and, while this pales in comparison to the Blackrock fees, it is still a stupid price to pay. You can get the same product from Vanguard or Fidelity for less than a third of this price.

The excess spread --- say 35bp to 43bp--- may not look like much, but at retirement time when you have just 400bp to draw down to live one each year, it is at least 8.75% of your income. That is one hell of a tax!

Project Due Date: Noon Wednesday Dec. 17

The UPenn Exam Schedule has our final scheduled for Wednesday Dec. 17 so t his date is the "fairest" day to have your projects due. It also maximizes the time you can invest in doing a great project. I'll also get them all graded and have the grades posted before I go of to Puerto Rico for a little winter holiday. Seems prefect!

Day 20: Rolling Statistics and Momentum Strategies

For 12th November 2008

It never pays to ignore what you know, so any forecast, strategy, VaR level, or performance measure needs to be constantly up-dated as new data arrives. The first part of our plan is to review the tools in S-Plus that make this easy. The main tool is aggregateSeries(). This is a very general tool that makes it convenient to do "rolling anything."

Moving Averages --- Simple Minded, but Not Silly

We'll also look at some of the most ancient tools of time series analysis, the exponential weighted average. This is an all-purpose tool that is often used in combination with other, more sophisticated, time series tools. One of the apparent difficulties in the use of moving averages (simple or exponential) is that one has to pick a "window" size. We'll discuss some ideas for dealing with this problem, including" Foster's Trick." This is something that it would be very worthwhile to explore in a final project.

We'll see how it is used in the MACD, which is reported in many graphical packages, including the free on-line chart service BigCharts.com

MACD and Other Price Level Favorites

MACD is goofy in some ways but it has fascinated me for a long time, because it so often looks like "it works." Unfortunately, formal tests with individual equities mostly come back with the verdict: "No extra cheese."

I keep looking for the context where MACD really does pay the rent. My sense is that it has a good chance of working well in currencies, and in style spreads --- say small cap value vs small cap growth. It might also be useful in making guesses about sector rotation. Exploration of one or more of these ideas might make a good project.

Momentum Strategies

Finally, we will look at a resource page on momentum strategies. It has a CitiGroup FX Advisors presentation, and summaries for a few leading academic papers on momentum. The CItiGroup piece is pretty lame by the standards of 434, but it is worth a brief look. If nothing else, it suggests that at least some of the competition is not to be feared.

Sidebar: MLPs

I started a little resource page on MLPs, or Master Limited Partnerships. These form a very interesting asset class with attractive non-standard features, including very fat (and pretty stable) dividends and favorable tax treatment. These benefits spring from the tax law view that an MLP is a "wasting asset," but this theory may not apply to many MLPs --- except as a handy tax law fiction.

Sidebar: Tops and Bottoms Identified by Sector Leaders?

A random web wag suggests that at the market tops the leading sector is consumer staples (say as reflected in XLP) and at market bottoms the leading sector is consumer discretionary (say as reflected in XLY). Naturally, this case is built on recent experience, and it does make modest sense. Is it something you'd like to bet on? I can't decide, but it is something that I'll keep in mind.

One of the things that I find interesting in this analysis is the use of the XLY/XLP ratio. There are lots of other contexts were such an idea my be just what one needs to stir the "missing non-linearity" it to the model.

There is a related theory that says that of all the goodies out there that might be counted on for reliable trending --- retail is the king. If you are looking for leading indicators, the retail index RLX may be a good shot.

Sidebar: Markets and Mindshare

The size of the world's bond market (55T?) and world's equity market (45T?) are comparable in a "Fermi sense." Historically, equities have clobbered bonds. Moreover, bonds are hardly risk free. For example, the bonds of the Weimar Republic became worthless, but the stocks did not. On a less dramatic scale, you can have a very rocky road with even a 30 year US Treasury --- a 1% rise in interest rates can cost you perhaps 25%, depending on the initial interest rate. So, why are there so many people, businesses, and governments who are happy to own bonds? How does this fit with our "counterparty theory" of strategic investing.

Sidebar: Stylistic Features of SP500 Returns

Wilhelmsson (2006) also deserves some class time. One nice feature of the paper is a break-down 1995-2000 and 2000-2005 of the fundamental features of the SP500 returns. These are very useful for calibration of one's intuition about returns --- and hence for "Fermi" calculations. This is his Table 3, and it is not his main message, of course. The main message is that it pays to deal with kurtosis (fat tails), but may not pay to deal with skewness (asymmetry about zero). One of the take-aways is that GARCH(1,1) driven by shocks that have the t-distribution is the best of breed given method of evaluation. We may not buy that method, but the conclusion may still hold up for us.

Sidebar: Be Short Vol and Expect Sad Days

Straddles, Nick Leeson, and the collapse of Barrings Ban

Sidebar: Fact or Artifact

There is a Seeking Alpha piece that reports on weekly returns of SP sectors versus the weekly returns on oil. They get that energy is positive (well, duh!) and everything else is negative --- with XLP being the most negative. Do you expect this relationship to hold up over time, or is it simply an artifact of the study period (which ended in October 2007).

Day 19: Comparing GARCH Family Members

For 9th November 2008

Now that we have a substantial family of GARCH models, how should we choose between them? The plan is to first consider some structural features, especially the connection to the Wold representation and our old bête noire --- stationarity.

One useful way to compare the many animals in the Garch Zoo is by looking at a plot called the "news impact curve." Given two models we first find appropriate values for the parameters of the models, say by fitting both to the same data. When then fix those coefficients and consider the the conditional variance as a function of the innovation epsilon_ t.

This function tells us how the two models will differ in the importance that they attach to a given shock. This measure is not perfect, since it speaks to just the impact of one shock. Still, it seems to be informative, and it is easy to implement (see e.g. S-Code Ex.)

The picture we get will give some intuition about which models "care" most about a negative shock versus a positive shock. Still, the pictures are not perfect, since it is not always easy to say which parameters values are "comparable" when one looks at radically different models. One way to make progress is to fit both models to the same data. Unfortunately, this begs another question; namely, the question of model specification.

Next, we consider non-normal drivers of the GARCH model. This is an important issue that makes the GARCH model much better than it would be otherwise. Still, the trick is old, going back to Bollerslev (1986).

Finally, we dig into a paper of Hansen and Lund which compares some 330 GARCH models. This is a heroic effort which we will be delighted to cover only from the summaries. Still, there is room to note a fundamental philosophical point. To compare one needs a criterion. How is one to choose among the potential criteria? My favorite is fitness for use, but this is not always feasible.

CAVEAT

I tend to "sell" the take-away from Hansen and Lund to be that "you don't need to look much further than GARCH(1,1), or perhaps EGARC(1,1)." I do believe this, but it is a little sophistic to argue this just from exercises like that done by Hansen and Lund. The problem is the criteria for judging the models. Hansen and Lund use a bund of them, but a eight inadequate measures are not all that much better than one. Also, the idea of ranking a zillion pretty similar models and then looking at the ranks --- well, that is clever, but it is also a bit sophistic.

Alternative Features of Merit

There is anther principle that I like. You could call it simulated verisimilitude. You fit the model, then simulate data from the model, then do EDA on your simulated series and your original data. If the EDA (and other logical) comparisons are not pretty close, then you have good reason to be unsatisfied with your model.

It is amazing to me how seldom this method is used by model builders in operations research, scheduling, logistics, transportation, etc. Those guys very often use models that have very little relation to the stylized facts of their business. In financial time series, we do at least have this part of the drill down pretty clearly.

Last Homework! This homework provides experience using a GARCH model to engage something that is of bottom line interest --- the relationship of risk and reward. As it is presented, it is reasonably straightforward. Nevertheless,t if you have time, you can use it to do a little exploring for your final project. It also provides a reminder of the very on-going importance of basic regression and EDA studies.

Approaching the End Game

On Monday the 17th the last homework comes in, then Wednesday the 19th and Monday the 24th will be "regular days." On Wednesday the 26th, the day before Thanksgiving, we will have our first round of "Final Project Proposals." The second and third rounds will be on the 1st and 3rd of December, our last days of class. The final projects themselves will be due on December 12 at noon.

Sidebar: Chicago Becomes "Booth" for $300M

David Booth co-founded Dimensional Fund Advisors to provide a keyboard of low cost but delicately sliced index funds that could reflect phenomena such as those one sees in the three factor model and earlier academic work. Good execution and thin margins led to a stellar reputation and $120B under management. DFA has always maintained close contact with academia and they have a research page that everyone should visit from time to time.

Mr. Booth did well enough with this service to be able at age 61 to give the University of Chicago Business School a little something.

Sidebar: Roll of Subjective Judgment in Risk Models

The NY Times article "In Modeling Risk, The Human Factor was Left out" adds a bit to our discussion of VaR models, especially those models that ignore "known but unobserved risks" such as the historical "peso problem" or the more recent "agency problems" of CDOs.

Sidebar: The "Silly Bid" and Structured Products

There is a curious strategy that has emerged in the last few months. You take some reasonably thinly traded stock and just place a "silly" bid --- say one that is 10%-20% below the market. Even now your bid is unlikely to be hit, but in this market, it is possible. Given that you have chosen a generic stock --- not a wounded rhino --- you should be very happy with the trade. I like this "trick" with structured products like NMQ. At present levels, NMQ is a SP500 Index asset but it is held mainly in retail accounts and the Amex market makers don't pay much attention to it.

Day 18: The "Leverage Effect" and the GARCH ZOO

For 6th November 2008

The GARCH model takes a major step toward a realistic statistical view of the noise in asset return series. Still, it is not perfect. In particular, the plain vanilla GARCH model responds symmetrically to either a negative or a positive shock. Historically, it is the case that a large negative shock has a more substantial impact on subsequent volatility than does a positive shock. A GARCH model cannot capture this phenomenon.

Fisher Black (partner with Myron Scholes in the Black-Scholes formula) called this phenomenon the "leverage effect" and the name has stuck. Black gave an interpretation of this empirical phenomenon from the point of view of the firms debt to market capitalization ratio. We'll do a Fermi calculation to see if this interpretation holds up as sturdily as the name.

One point to note: Black's leverage story may seem to contradict the Modigliani-Miller Theorem. If it did, it would not particularly bother me. Still the problem is worth pondering. I'll argue the view that there is no contradiction because the Modigliani-Miller assertion is about value, and Black's leverage story is about volatility. Now volatility does effect value, but subtlety --- through volatility drag from our perspective, but surely not enough to make us regard the MMT and Fisher's leverage effect as contradictory.

Cultural Note: Franco Modigliani --- an Italian-American --- pronounced the "dig" in his name and won the Nobel prize in 1985. Amedeo Modigliani --- an Italian painter --- pronounced gli as "li" in the Italian fashion and lived a brief life that was textbook Bohemian.

We'll then look at the models that attempt to cope with the so-called leverage effect. Most of our attention will be given to Nelson's EGARCH model, or exponential GARCH model. This is the "next step" model that has rather reasonably stood the test of time. It is definitely useful by both academic and practitioners. It definitely has its uses, though it does not provide nearly as big an increment to our toolkit as GARCH itself.

After EGARCH there were many other models that attempted to deal with this or that stylistic fact that is not well modeled by GARCH. Naturally, one eventually faces a certain law of diminishing returns. Still, it pays to know about at least a few of these.

We'll also look at some relevant examples in S-Plus. It does indeed turn out that when you fit a model like EGARCH to the returns of an individual stock, you are very likely to get a significant value for the leverage parameter.

It's not easy to say what this really means to us in an investment context, but it is certainly worth thinking about.

Leverage Effect not a Leverage Effect

For year's I have argued that Black's interpretation of the "leverage effect" as a "leverage effect' didn't really make sense, and II figured that everybody knew this.

Turns out that there was still a paper to be written, so if you want (substantially) more than what comes with our Fermi calculations, you can look at an informative 2000 paper of Figelwski and Wang.

Sidebar: Risk and Reward

There is a piece on the risk-reward trade-off posted at CXO that is worth a quick look. Some parts of the piece are confusing, but it puts interesting questions into play. The introductory story should make sense to you, and, if you get interested the original paper is worth a look.

The big question is "Do you get compensated for taking incremental risks --- or is it the case that for any given asset incremental risk (as measured by "volatility") is an a priori bad thing?"

In the classical stocks versus bonds story, we see historically a very reassuring compensation for risk taking, but through time and within one asset class the story comes close to reversing itself. You'll get to explore this in HW9.

Also, from CXO there is a nice list of assertions relating volatility and excess return. This is a good list to think about as you ponder your final project, which we will start discussing today.

Day 17: ARCH and GARCH

For 3th November 2008

The ARIMA models underpin a large part of the theory of time series, but they have an Achilles heal when applied to financial time series --- the conditional variances of ARIMA models do not change as time changes.

For financial time series, this is in violent contradiction to reality.

One of the most fundamental stylistic facts of asset returns is that there is "volatility clumping" --- periods of high volatility tend to be followed by periods of high volatility, and periods of low volatility tend to be followed by to be followed by periods of low volatility.

The ARCH and GARCH models were introduced to remedy this situation, and they have led to models that are much more representative of financial reality. Our plan will be to develop these models as they evolved, first looking at why they are really needed. We'll also look at the tools in S-Plus for handling GARCH models, either in simulation or in fitting.

Finally, we'll discuss some original sources, notably a review article by Robert Engle called GARCH 101. The notation used in this piece is no longer the standard notation, and some bits are best taken with a grain of salt. In particular, given what we know now, Engle's discussion VaR "optimistic." Still it is definitely fun --- and instructive---- to take a look.

Another paper we might discuss briefly is Engle's paper with Andrew Patton "What Good is a Volatility Model?" Ironically, this paper has the "tell" that I have mentioned in class, namely it uses the Dow (OMG!) as its illustrative price series. I don't know what motivated this choice, and I find it a little less serious than I would have hoped.

A positive feature of the paper is that it gives a brief list of "stylized facts," a very important notion to which we will start paying more systematic attention.

Sidebar: TIPS Spread and Money Manager Survey

"Nor do the managers worry about runaway inflation. They see prices rising by 3.28% this year, but by a lesser 3.02% in 2009." --- from the Barrons Big Money Poll 11/3/08

"TIPS yields indicate investors are betting consumer prices will fall. Five-year TIPS yielded 0.31 percentage points more than Treasuries of similar maturity this week." --- Bloomberg 11/1/2008

So, we have a horse race. Do you believe the consensus of money managers or do you believe the TIPS/Treasury spread?

My own bet is that you'll do much better with a hold to maturity 5 year TIP than the corresponding treasury --- even if there is not much difference in the first two years. Stocks "should" beat both over a five year period, but that horse is not in this race.

Sidebar: TrimTabs, Money Flows, and "Bottoms"

It's November 1st today, and this makes it interesting to look at the Market Letter of October 1 Charles Biderman at TrimTabs --- the flagship research firm on money flows. This work is interesting to me, even though I have confessed to something close to a learning disability concerning flows "into or out of stocks."

Flows into futures (though symmetric) are less paradoxical --- and money market flows are (probably) not paradoxical at all. Golly, mutual fund flows always make perfect sense, even though "stock market flows" do not make sense to me --- except for the transitions of IPOs, repurchases, privatizations, and a few other special cases --- that go beyond "normal" purchases and sales.

I respect the firm and Biderman, so it is interesting how one of the worst months in history was so misread ex ante. This is especially curious since fund flows do seem to have been a big driver for the month.

"When public companies are net buyers while individuals are heavy net sellers, the market is making a bottom": this is an interesting feature of the TrimTabs Liquidity Theory.

Sidebar: The Great Gasparino Mystery (3:38pm Oct 30, CNBC)

[Approximate Dialog between Dylan Ratigan and Charles Gasparino --- as real time blogged]

Ratigan: Charlie, what have you got?

Gasparino: What have I got?

Ratigan: Yeah...so give us the story.

Gasparino: What have I got? What have I got? What have I got?

Lee: Charlie, just tell us!

Gasparino: What have I got?

Ratigan: Charlie, we've got limited time.

Gasparino: What have I got? What I got is shoot for the capitalism.

Ratigan: 'Shoot for the capitalism'? What?

Gasparino: What have I got?

Ratigan: Okay, not really sure what just happened there.

Charlie Gasparino is a "movie star" for market wonks --- professional and amateur alike. This time he seems to have taken an unfortunate slide toward the Nick Nolte side of celebrity things, but who really knows?

Rumors will surely fly. There is a blog with an (imperfect) UTube link. Judge for yourself. We'll follow the fallout. There are also earlier interviews with Charlie on better, yet still revealing, days.

Up-side Alternative Suggestion: Maybe a CNBC Lawyer told Charlie he could not go with "What I got." Then, an exasperated Charlie just mumbled up his air time. To me, this does not quite compute. Charlie is slick enough to say, "I had a story, but I am just now informed by "legal" that I have to put a lid on it. We'll sort it out and get back to you."

Follow-up: On Friday Oct 31 Charlie and Dylan had their 3:35 meeting and --- after doing some regular business ---they just made fun of the Thursday contre-temps and Charlie's YouTube notoriety. This doesn't quite wash.

Follow-up: Equity Help Desk has a plausible story, without rehab implications.

Sidebar: Mean Reversion vs Momentum

Essentially every quantitative strategy depends on a view that is either "trend following" --- that is a momentum strategy , or "trend reversal" --- that is mean reversion strategy.

Between the two, there is always a finely pitched battle. It seems to me that the momentum story has more reported successes. Still, there are situations where the mean reversion case can be made. One of these was mentioned in the Granger article covered last time.

As a variation on the strategy reviewed there, take any set of say 100 stocks. Now on each day, buy the 3 that are off the most at the close, and hold these stocks for 10 days. Now, compare this strategy to the comparable market buy-and-hold strategy. How do you do? Here, by the way, you might take your transaction cost to be 5 basis points on each leg of the trade. This is realistic if your trades are small enough to avoid market impact cost.

The biggest potential "bug" in such a study is that your real-world "buy on close" price may have some slippage from the "print" close that you find in the historical data.

Notation --- Possible Pedantry vs Certain Sloppiness

I mentioned in class an example of a lecturer at a distinguished university who took such "liberty with notation" (the charitable interpretation) as to simply boggle the mind. It seems only fair that I provide a link --- which I will soon make dead. Just go to page 5 and ask yourself, "How could the students not be hopelessly confused?" Incidentally, I don't wish to pick on these authors (well, maybe); rather I want to point out that good notation makes for good reasoning.

Actually, it is more certain that bad notation makes for bad reasoning.

Physicists, chemists, and astronomers, sometimes scrape along with dodgy notation --- but only because they are much smarter than we are --- and more accustomed to living with notational ambiguity.

In fact, even these princes of science have often confuse themselves unnecessarily for years. Rigor really is a great simplifier.

Finally, to be super charitable, I will later present a computation that I learned from the delinked notes. Yes, you can learn from even the most muddled sources.

I find this consoling. No matter how daft I may be --- or may become ---I am reasonably confident that I will not damaged your minds irreparably.

Sidebar: Purchase Price Parity and the Big Mac Index

The Economist this week has come out with one of its perennial favorite articles, the world survey of exchange rates and their comparison to PPP as reflected in the price of a Big Mac.

Sidebar: A More Positive Case for VaR and a Spin on Subjective Input

There is a WSJ piece (temporarily misplace) that sings high praise for the use of VaR at GS and its value in helping to steer them out of some of the subprime mess. They eventually get hammered by the systemic issues, but at least they had a moment of reprieve. Eventually I'll have an essay on VaR.

Day 16: Switching Regressions, Non-Linearity, Forecastability, and Cost-Benefits of Subjectivity --- and, oh, Tells!

For 29th October 2008

Our main goal is to review a classic discussion paper by Clive Grainger, "Forecasting Stock Market Prices: Lessons for Forecasters."

Grainger shared the 2003 Nobel Prize in economics and his contributions find few equals in the world of econometrics.

Granger's old paper has benefits for us even though at this point the it is rather dated. One benefit is that it can be 95% understood at the level of Stat 434. Second, and more persuasively, it suggests some potentially useful ideas that even now have not fully explored.

As a caveat, his introductory comments on martingales and the EMH (and a few other things) are way off the mark. For example, if asset prices were martingales as the introduction considers, then only risk-seeking gamblers would invest.That is just silly.

This part of t he paper can be fixed with just a small correction. For example, one can use a I mentioned alternative earlier. Specifically, the ratio of an asset price to the market price may be more feasibly viewed as a martingale --- or even a supermartingale which you recall is a "bad" game. This makes the assertion logical. Unfortunately, it remains untestable.

At other places in the paper, we have to be concerned about data quality, or stationarity, or data relevance. For example, one of the papers that Granger discusses uses market returns back to 1896. For me, this is just too far past the "use by date".

Similarly, at one place Granger looks at transaction costs of 0.5% or ever 1%. Nowadays, this is a silly level of transaction costs for the assets in question --- except in the remotely relevant situation of market impact costs. In more common (but still special) situations, you are even paid to trade; that is, you make money trading, even if you just break even on the trades. This sounds weird, but I will explain. It is a little bit like being a shill in a poker game. Sidebar: The Wiki piece on shills looks only at the negative side. There really is a positive side too!

Nevertheless less, if anyone is looking for advice about how to have better luck forecasting asset returns, this is a very sensible place to begin.

Note: Citation Searches

When you find an article that you like (or even one you don't like), you can find more recent articles that follow up on it by doing a citation search. This is typically a much more efficient way to find relevant research than just by looking up a topic. In particular, if you look up a topic that is too broad --- like forecasting --- almost no one can thread his way through the forest. Citation searches are a very powerful research trick.

Note: S-Plus Tools For Rolling Regressions

We may also discuss the tools that are available in S-Plus for dealing with dynamic regression. Rolling regressions and weighted rolling regressions are a staple in many of the Stat 434 final projects, but at this stage you can probably learn everything that you might need about these tools just by working through the code box example.

Note: Risk Free Rates

For a CAPM style modeling exercise, one needs "risk free rate." Exactly which rate one might choose is open to debate, but 30 day treasury yields are usually appropriate. When you put any rate into the regression you will naturally have to make sure you are comparing apples and apples --- i.e. daily stock returns and daily risk free returns. To convert treasury yields to daily yields, you can use the conventional 360 day year. For data resources you have several options.

Sidebar: The Old Bellwether Idea --- It's now Now the Apple Tell

For the longest time people would look to GM (LOL!) and later IBM as "bellwether" indicators of the market. That is, these were viewed as leading indicators of the whole market. Mr. Love-Him-Hate-Him Cramer put it out on 10/28/2008 that Apple is the new "bellwether." Is this baloney, or is it cheese?

BTW, "cheese" is a 434 term of art that stands for "excess returns." This friendly term has not been used much this year, perhaps as an apology for past year abuses --- or as an acknowledgement that there have not been many excess returns this year.

Sidebar: Uses of Subjective Information

In science and engineering there is a tradition of working hard to minimize subjective content of models and analyses --- but even there one has to admit that many design choices are based on subjective information. There is a phenomenon in economics called "physics envy" and this is one of sources of pressure for analysts to minimize subjective input into financial and economic models. The downsize is that this leads to more and more weight being place on historical observations. As we know from the discussion of the Peso Problem, such back-looking empirical estimates may ignore some serious economic facts.

This brings us to the thorny issue of subjective input in to models like those that are used in VaR calculations. It is clear to me that subjective input would have provided at least some improvement on the VaR models that have blown up over the last year. If one does advocate subjective input, it's a good idea to give a periodic review of the cognitive biases which can be as real --- and as dangerous --- as the "path-focused objective myopia" which one might hope to ameliorate with the inclusion of at least some explicit subjective inputs.

Sidebar: Regarding CAPM and Other Puzzle --- What Changes a Mind?

“Children do eventually renounce their faith in Santa Claus; once popular political leaders do fall into disfavor…Even scientists sometimes change their views….No one, certainly not the authors, would argue that new evidence or attacks on old evidence can never produce change. Our contention has simply been that generally there will be less change than would be demanded by logical or normative standards or that changes will occur more slowly than would result from an unbiased view of the accumulated evidence.” ---Nisbett and Ross (1980), quoted by Hong and Stein (2003).

Incidentally, this quote is consistent with the notion of confirmation bias which asserts that a person holding a view is more likely to be attentive to evidence that supports his view than evidence that does not. Confirmation bias is a feature of human psychology that has been demonstrated in a great variety of experiments.

Sidebar: Remembering: October 30, 1961

Tsar Bomba was detonated at 11:32 a.m. on October 30th, 1961 over Novaya Zemlya Island in the Arctic Sea. With a lead tamper, the bomb had a yield of 50-60 Megatons, more than ten times the explosive force of all of the explosives used in the Second World War --- including the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Tsar Bomba was a very clean bomb, as essentially all of the fallout would come to rest on the USSR. With a more "traditional" design using uranium tamper, the yield would have been expected to be100 megatons. The Tsar Bomba is the most powerful bomb to be detonated on Earth --- so far.

Vestigial Sidebar: Volatility Drag

We may also revisit the formula for volatility drag, though I think this is well-known to you now. The spin I do not want you t miss is that volatility drag may offer some explanation of why the "2x" leverage funds do not provide returns that are as large as one might have expected given the returns of the underlying asset.

Day 15: Time Series Regression and Applications to CAPM

For 27th October 2008

The plan mostly focuses on the natural extension of ordinary least squares regression (OLS) to financial time series. Still, there are new topics, such as the likelihood ratio test and the AIC criterion. We'll particularly look at AIC, AIC weights, and the way to use these to combine forecasts.

We'll look at the nuances of the model and its associated tests. We may also cover a MSFT/CAPM example that is bundled with Finmetrics, but you can just as well look at this by yourself.

One of the most famous models that fits into this context is the 1992 Fama-French Three Factor model. This is the model which for many (but not all) signaled the "death of the CAPM." Parallel Mark Twain's line, the rumors of the death of CAPM may have been greatly exaggerated. Still, the true believers are starting to face a sea of troubles that are almost as tough as the ones face by those who preferred had a hard time with heliocentrism, but comparably sure experiments are much harder to come by.

The Wikipedia article on Fama describes the three factor model, and it also has useful links, including one to the original FF92 paper and a good humored one to a Dartmouth humor magazine.

If you do look at the original lFF92 article you will see that there is a fair amount of technology there which we have not engaged. Still, with the tools we do have you can tell very similar stories. The basic tale is pretty robust. It's time to list it as one of our "stylistic facts."

Maximum Likelihood and the ML Ratio Test

Basically all the test that you have seen in all of the statistics courses that you have taken are obtained by on general method, and they are all what is called a maximum likelihood ratio test.

The computations behind these tests are a basic part of other statistics courses, but we still to well to review a bit of this theory. In particular, it gives us the chance to nail down the very fundamental notion of the likelihood. This is critical for maximum likelihood estimation, for the likelihood ratio test, and for other cool stuff like the AIC, which comes up next.

Akaike's Information Criterion and Model Averaging

The Akaike Information Criterion (or AIC) is perhaps the most widely applied criterion for model selection.

For my own account, I am not a huge fan of AIC. The main problem is that in many cases one assumes at least as much going in as one hopes to infer coming out. In pure model selection there may be some net gain in most cases, but, since there can be loss in some cases, it is not clear that one wins over all.

Still, the AIC is out there, and it mostly seems to point in the right direction. It's probably worth consideration in most contexts, provided that one does not get too carried away.

Model Averaging: A Practical Alternative to Model Selection

If you are interested in using your model as a forecast, you may be able to side-step the problem of model selection. Rather than simply chose model A or model B to make your forecasts, you can instead consider an appropriate average of the forecasts given by the two (or more models).

Foster's Trick For Model Averaging

There are many rules one can pose for averaging the forecasts given by a set of models. You could just take the simple average, or you could take a weighted average where the more accurate model is given a larger weight. A still more principled idea that I learned from Dean Foster is to use regression. Here one takes the forecasts of the models and regresses the observed returns against these forecasts. One can then use the regression coefficients as "weights" for the combined model. Here we use the quoted because the weights can be negative and need not add up to one, so this method is not strictly an averaging method.

Naturally this idea must be combined with good sense. The forecasts given by your original models are quite likely to be highly correlated, so this regression problem can be ill-conditioned. My advice would be to consider this as a exploratory tool. There is no reason at all why you cannot stir in your own judgment.

The "Best" Criterion --- Fitness for Use

The model that is best is the one that "works" best for you. Ironically, this criterion is not often discussed. I have written a bit about this, and eventually I will write more. The whole notion of a model is one that deserves a richer --- and more philosophical --- view that is common in statistics courses.

Sidebar: Surprises with Qualified and Non-qualified Dividends

The crash of Fall 2008 created some eye-popping dividend yields, but it also created some quirks that may surprise investors who chase those yields. The so-called qualified dividends are those on US tax paying corporations and these are taxed at a maximum federal rate of 15% but non-qualified dividends (such as those on REITs) are taxed at a maximal 35%. The surprise is that for the dividend to be qualified the corporation must pay federal corporate tax, and, with earnings in the tank, many firms will not pay taxes. Thus, those "juicy" dividends stand ready to be taxed at the higher rate --- if indeed they are paid at all.

Sidebar: "120/20 Good Buddy"

Among the strategies that now have the public ear are the 120-20 strategies ---- leverage up 20% on the long side and off-set this leverage by going short for an amount of 20%.

Naturally, such a strategy would be nuts --- unless you could pick winners for at least part of your up-position and pick mostly under-performers for your short position. As a retail investor, you would also face an 8% margin cost headwind on the 20% that you are leveraged and the headwind of any dividends to be paid on the downside.

Thus, for an individual investor replication of a 120-20 strategy is a non-starter.

As an institutional investor, your long position will cost LIBOR and a bit and your short position will pay LIBOR minus a bit, so for professionals the whole game becomes modestly feasible.

Thus, professionals have the opportunity to let you in on this game --- for a modest fee, of course. This is a good trick all by itself, but the 120/20 pitch has a ready listening. You can look at some of the recent pitches.

My own view is that these retail issues are not good deals, but I am open to arguments on the question. If you are looking for a final project, you might want to consider a project that plays off of these funds.

Sidebar: "Is RSP a Stinker?"

Just as a side note, you might want to think about a project that plays RSP versus MDY or VO. My best guess is that RSP is almost a dominated asset, or at least a stochastically dominated asset. My guess is that you will almost always be able to beat RSP with MDY (or at worst a blend of MDY and SPY).

Yet more strangely, I bet you can dominate MDY with VO. This needs to be checked, but if it pans out then one finds yet another place where investors could save a few tens of millions of bucks (per year)..

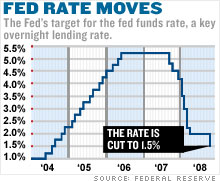

Sidebar: Fed Funds Rate Cut on Stage

Everyone expects a move this week, but there isn't a lot of wiggle room left.

Day 14: VaR --- The Sad Story

For 22th October 2008

The first (and main) part of the plan today is to look first at the most widely used tool for expressing risk exposures:VaR, --- or Value at Risk.

As I said even before the 2007 course blog: "There is much wrong with the way VaR is used and calculated --- even in the most enlightened firms. Some implementations are close to (1) a hoax or (2) at least naively self-delusional. "

Still, VAR used almost universally. Moreover, the vast majority of implementers are sincere they have done their best.

The people I hold responsible for the destruction caused by VAR are those who said, "Everyone else has good Value at Risk measures. Either you guys come up with a system that works, or I'll get someone who can." In such an organizational situation, you are guaranteed to get bogus analyses --- all of which will agree very comfortably agree with all the other delusional models. This is sad, but very human --- the mechanism of social proof is as universal as any phenomenon one can imagine.

Again, humbly quoting myself from the 2007 blog, "If one could simply bet against run-of-the-mill VaR estimates, one would not need to look for other investments. This would be ... a veritable paradise of Black Swans, vastly more lucrative than those (too rare) Black Swans that stingy options traders occasionally provide."

Why, Oh Why, Is this So?

There are two virtually insurmountable problems with VaR as it is calculated in most firms. These are the "Peso Problem" and the "everything is correlated at the extremes problem. " There is also a less overtly dangerous but still unavoidable problem I call "Tukey's Biased Estimate of Variance."

The "Peso Problem" is a standard part of economic lore ---- but it is steadfastly ignored by essentially ALL VaR models.

The "correlation problem" has also been widely understood for a long time. It was one of the forces that led to the demise of LTCM. It was one of the forces in the Niederhoffer's first blow up after the Asian Crisis of 1994. My favorite example actually goes back to the great flood of 1927, and I'll tell that story in class.

Still, the" correlation problem" is ignored in 99.9% of VaR models.

Finally, how about Tukey's Estimate? I'll elaborate in class, but --- it's ignored. Why? Because it would force everyone to bring down their leverage. Well, in October 2008, we have the strong sense that bringing down the leverage would have been smart for every bank that did. Sad, but true.

John Tukey understood all of this, even before the ideas came into play in a financial context.

With a barrel-chested sotto voce rumble, he would say, "The variability that you have seen is always an under estimate of the true variability." In our context, where volatility and variability are cognates, Tukey is on one side, and the world's VaR models are on the other.

My money is on Tukey.

Still, many firms are getting better at VaR, and we just need to have evolution play its role. Though many individuals in many firms will kick and scream, the big firms with the best VaR models (and other risk controls) will be survivors. As the "subprime" story plays itself out, we are likely to find that many firms had VaR estimates that were pure garbage. It seems inevitable that some measure like VaR will always be with us --- and it seems that sometime again in the future it will greatly fail us.

Extreme Value Distributions --- Use at Extreme Risk

On the more technical side, we'll look at extreme value theory, which is one of the tools that theoreticians always seem to want to trot out when there is a discussion of big market moves. The mathematics of the extreme value distributions is interesting, but for several reasons extreme value theory doesn't deal with the reality of extreme market moves.

We'll discuss the Gumbel (or Fisher-Tippet) distribution in class. It comes out of a beautiful limit theorem, and it is the leading example of what are know as extreme value distributions. Sadly --- and in stark contrast to the Central Limit Theorems --- there is a major disconnect with any level of honest practice.

You will see from a homework problem that the convergence is excruciatingly slow even in the ideal case of normally distributed random variables. There are people who have advocated the use of this distribution in financial practice. It has even been used as part of the Tokyo building code. These applications are bogus, bogus, bogus.

Still, extreme value distributions are worth learning about. There probably are special contexts where they are applicable, and they have a undeniable charm. Also, they are part of the common language, and any time "extreme" events are discussed, they are likely to be drawn into the conversation. When this happens, be prepared to be skeptical.

As a sidebar, this also give us a chance to discuss the some core ideas of simulation, including the rejection method and the inverse probability transform method.

Risk-Adjusted Returns

FInally, we will look at some suggestions that have been made for comparing returns on a risk-adjusted basis. These are useful --- certainly better than simple raw returns --- but they still can lull us into forgetting the peso problem. The Wiki piece on the Sharpe Ratio gives the basic definition, though it is a little short on motivation. The piece also has links to a bunch of related ratios, some of which were new to me. Almost all of the final projects will need to deal with risk-adjusted returns in one way or another. At some point in life, everyone should read Bill Sharpe's Original Article.

Finally, here is a somewhat dated table of Sharpe Ratios from our friends at Merrill Lynch. This should be considered in light of the Bloomberg piece on their write-downs in Oct 2007 (i.e. ONE YEAR AGO)..

Sidebar: Related Material